Whatever shock Mrs. Springer experienced at my aunts appearance, she considerately concealed. As for myself, I saw my aunts battered figure with that feeling of awe and respect with which we behold explorers who have left their ears and fingers north of Franz- Joseph Land or their health somewhere along the Upper Congo.

My Aunt Georgiana had been a music teacher at the Boston Conservatory, somewhere back in the later sixties. One summer, while visiting in the little village among the Green Mountains where her ancestors had dwelt for generations, she had kindled the callow fancy of my uncle, Howard Carpenter, then an idle, shiftless boy of twenty-one. When she returned to her duties in Boston, Howard followed her, and the upshot of this infatuation was that she eloped with him, eluding the reproaches of her family and the criticism of her friends by going with him to the Nebraska frontier.

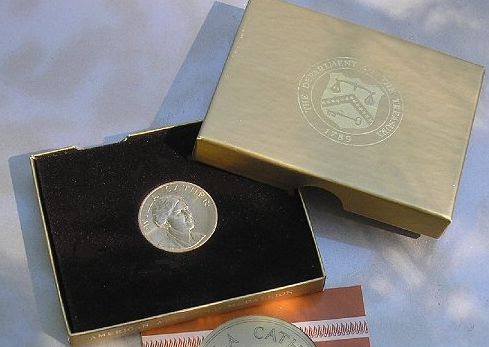

Carpenter

Carpenter, who, of course, had no money, took up a homestead in Red Willow County, fifty miles from the railroad. There they had measured off their land themselves, driving across the prairie in a wagon, to the wheel of which they had tied a red cotton hand-kerchief, and counting its revolutions. They built a dugout in the red hillside, one of those cave dwellings whose inmates so often reverted to primitive conditions. Their water they got from the lagoons where the buffalo drank, and their slender stock of provisions was always at the mercy of roving Indians. For thirty years my aunt had not been farther than fifty miles from the homestead.

I owed to this woman most of the good that ever came my way in my boyhood, and had a reverential affection for her. During the yeant when I was riding here for my uncle, my aunt, after cooking the three : meals the first of which was ready at six oclock in the morning and putting the six children to bed, would often stand until midnight at her ironing-board, with me at the kitchen table beside her, hearing me recite Latin declensions and conjugations, gently shaking me when my drowsy head sank down over a page of irregular verbs.

It was to her, at her ironing or mending, that I read my first Shakespeare, and her old textbook on mythology was the first that ever came into my empty hands. She taught me my scales and exercises on the little parlor organ which her husband had bought her after fifteen years during which she had not so much as seen a musical instrument. She would sit beside me by the hour, darning and counting, while I struggled with the “Joyous Farmer.” She seldom talked to me about music, and I understood why. Once when I had been doggedly beating out some easy passages from an old score of Euryanthe I had found among her music books, she came up to me and, putting her hands over my eyes, gently drew my head back upon her shoulder, saying tremulously, “Dont love it so well, Clark, or it may be taken from you.”

Read More about The First Crusade part 25