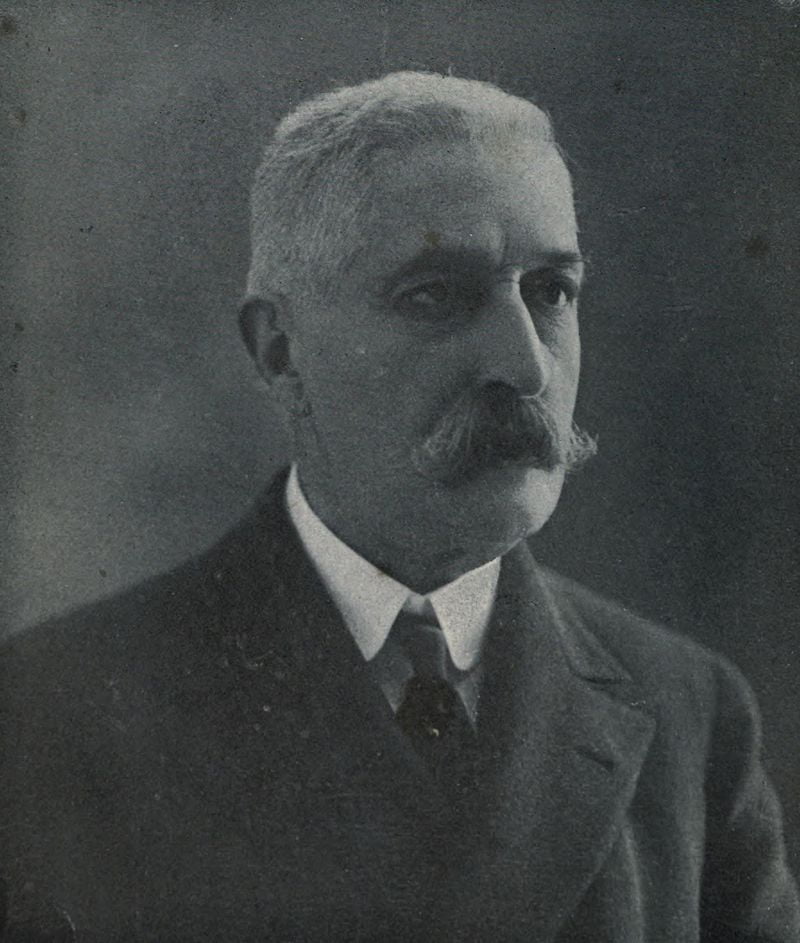

Giovanni Verga (1840—1922)

With Verga we find ourselves in modern times. The dawn of the Nineteenth Century found Italy in the full flood of that romanticism that was popularized by Byron and Scott. The figure of Manzoni dominated Italian fiction until the end of the Nineteenth Century.

Verga was born in Catania, Sicily, in 1840. His most significant work is his stories of Sicilian peasant life. The most celebrated is Cavalleria Rusticana, which was later adapted as the libretto of Mascagnis opera. Even the music has not entirely deprived the tale of its moving power. Verga is reckoned as one of the forerunners in the modern Italian dramatic movement.

The present version is translated by Frederic Taber Cooper. Co-pyright, 1907, by P. F. Collier and Son, and here reprinted by permission of P. F. Collier & Son Company.

Cavalleria Rusticana

After Turridu Macca, Mistress Nunzias son, came home from soldiering, he used to strut every Sunday, peacock-like, in the public square, wearing his riflemans uniform, and his red cap that looked just like that of the fortune-teller waiting for custom behind the stand with the cage of canaries. The girls all rivaled each other in making eyes at him as they went their way to mass, with their noses down in the folds of their shawls; and the young lads buzzed about him like so many flies.

Besides, he had brought back a pipe, with the king on horseback on the bowl, as natural as life; and he struck his matches on the back of his trousers, raising up one leg as if he were going to give a kick.

But for all that, Master Angelos daughter Lola had not once shown herself, either at mass or on her balcony, since her betrothal to a man from Licodia, who was a carter by trade, and had four Sortino mules in his stable. No sooner had Turridu heard the news than, holy great devil! but he wanted to rip him inside out, that was what he wanted to do to him, that fellow from Licodia. However, he did nothing to him at all, but contended himself with going and singing every scornful song he knew beneath the fair ones window.

“Has Mistress Nunzias Turridu nothing at all to do,” the neighbors asked, “but pass his nights in singing, like a lonely sparrow?”

At last he came face to face with Lola, on her way back from praying to Our Lady of Peril; and at sight of him she turned neither white nor red, as though he were no concern of hers.

Read More about The Matron of Ephesus 2